This article is about the field of science. For other uses, see Physics (disambiguation).

| Physics | |||||

| |||||

| Mass–energy equivalence | |||||

History of physics

| |||||

Physics is one of the oldest academic disciplines, perhaps the oldest through its inclusion of astronomy.[6] Over the last two millenia, physics was a part of natural philosophy along with chemistry, certain branches of mathematics, and biology, but during the Scientific Revolution in the 16th century, the natural sciences emerged as unique research programs in their own right.[7] Certain research areas are interdisciplinary, such as mathematical physics and quantum chemistry, which means that the boundaries of physics are not rigidly defined. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries physicalism emerged as a major unifying feature of the philosophy of science as physics provides fundamental explanations for every observed natural phenomenon. New ideas in physics often explain the fundamental mechanisms of other sciences, while opening to new research areas in mathematics and philosophy.

Physics is also significant and influential through advances in its understanding that have translated into new technologies. For example, advances in the understanding of electromagnetism or nuclear physics led directly to the development of new products which have dramatically transformed modern-day society, such as television, computers, domestic appliances, and nuclear weapons; advances in thermodynamics led to the development of industrialization; and advances in mechanics inspired the development of calculus.

Contents |

Scope and aims

For example, the ancient Chinese observed that certain rocks (lodestone) were attracted to one another by some invisible force. This effect was later called magnetism, and was first rigorously studied in the 17th century. A little earlier than the Chinese, the ancient Greeks knew of other objects such as amber, that when rubbed with fur would cause a similar invisible attraction between the two. This was also first studied rigorously in the 17th century, and came to be called electricity. Thus, physics had come to understand two observations of nature in terms of some root cause (electricity and magnetism). However, further work in the 19th century revealed that these two forces were just two different aspects of one force – electromagnetism. This process of "unifying" forces continues today, and electromagnetism and the weak nuclear force are now considered to be two aspects of the electroweak interaction. Physics hopes to find an ultimate reason (Theory of Everything) for why nature is as it is (see section Current research below for more information).

Scientific method

Physicists use a scientific method to test the validity of a physical theory, using a methodical approach to compare the implications of the theory in question with the associated conclusions drawn from experiments and observations conducted to test it. Experiments and observations are to be collected and matched with the predictions and hypotheses made by a theory, thus aiding in the determination or the validity/invalidity of the theory.Theories which are very well supported by data and have never failed any competent empirical test are often called scientific laws, or natural laws. Of course, all theories, including those called scientific laws, can always be replaced by more accurate, generalized statements if a disagreement of theory with observed data is ever found.[9]

Theory and experiment

Main articles: Theoretical physics and Experimental physics

Theorists seek to develop mathematical models that both agree with existing experiments and successfully predict future results, while experimentalists devise and perform experiments to test theoretical predictions and explore new phenomena. Although theory and experiment are developed separately, they are strongly dependent upon each other. Progress in physics frequently comes about when experimentalists make a discovery that existing theories cannot explain, or when new theories generate experimentally testable predictions, which inspire new experiments.Physicists who work at the interplay of theory and experiment are called phenomenologists. Phenomenologists look at the complex phenomena observed in experiment and work to relate them to fundamental theory.

Theoretical physics has historically taken inspiration from philosophy; electromagnetism was unified this way.[10] Beyond the known universe, the field of theoretical physics also deals with hypothetical issues,[11] such as parallel universes, a multiverse, and higher dimensions. Theorists invoke these ideas in hopes of solving particular problems with existing theories. They then explore the consequences of these ideas and work toward making testable predictions.

Experimental physics informs, and is informed by, engineering and technology. Experimental physicists involved in basic research design and perform experiments with equipment such as particle accelerators and lasers, whereas those involved in applied research often work in industry, developing technologies such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and transistors. Feynman has noted that experimentalists may seek areas which are not well explored by theorists.[12]

Relation to mathematics and the other sciences

This parabola-shaped lava flow illustrates Galileo's law of falling bodies as well as blackbody radiation – the temperature is discernible from the color of the blackbody.

Physics relies upon mathematics to provide the logical framework in which physical laws may be precisely formulated and predictions quantified. Whenever analytic solutions of equations are not feasible, numerical analysis and simulations may be utilized. Thus, scientific computation is an integral part of physics, and the field of computational physics is an active area of research.

A key difference between physics and mathematics is that since physics is ultimately concerned with descriptions of the material world, it tests its theories by comparing the predictions of its theories with data procured from observations and experimentation, whereas mathematics is concerned with abstract patterns, not limited by those observed in the real world. The distinction, however, is not always clear-cut. There is a large area of research intermediate between physics and mathematics, known as mathematical physics.

Physics is also intimately related to many other sciences, as well as applied fields like engineering and medicine. The principles of physics find applications throughout the other natural sciences as some phenomena studied in physics, such as the conservation of energy, are common to all material systems. Other phenomena, such as superconductivity, stem from these laws, but are not laws themselves because they only appear in some systems.

Physics is often said to be the "fundamental science" (chemistry is sometimes included), because each of the other disciplines (biology, chemistry, geology, material science, engineering, medicine etc.) deals with particular types of material systems that obey the laws of physics.[8] For example, chemistry is the science of collections of matter (such as gases and liquids formed of atoms and molecules) and the processes known as chemical reactions that result in the change of chemical substances.

The structure, reactivity, and properties of a chemical compound are determined by the properties of the underlying molecules, which may be well-described by areas of physics such as quantum mechanics, or quantum chemistry, thermodynamics, and electromagnetism.

Philosophical implications

For more details on this topic, see Philosophy of physics.

Physics in many ways stems from ancient Greek philosophy. From Thales' first attempt to characterize matter, to Democritus' deduction that matter ought to reduce to an invariant state, the Ptolemaic astronomy of a crystalline firmament, and Aristotle's book Physics, different Greek philosophers advanced their own theories of nature. Well into the 18th century, physics was known as natural philosophy.By the 19th century physics was realized as a positive science and a distinct discipline separate from philosophy and the other sciences. Physics, as with the rest of science, relies on philosophy of science to give an adequate description of the scientific method.[14] The scientific method employs a priori reasoning as well as a posteriori reasoning and the use of Bayesian inference to measure the validity of a given theory.[15]

The development of physics has answered many questions of early philosophers, but has also raised new questions. Study of the philosophical issues surrounding physics, the philosophy of physics, involves issues such as the nature of space and time, determinism, and metaphysical outlooks such as empiricism, naturalism and realism.[16]

Many physicists have written about the philosophical implications of their work, for instance Laplace, who championed causal determinism,[17] and Erwin Schrödinger, who wrote on quantum mechanics.[18] The mathematical physicist Roger Penrose has been called a Platonist by Stephen Hawking,[19] a view Penrose discusses in his book, The Road to Reality.[20] Hawking refers to himself as an "unashamed reductionist" and takes issue with Penrose's views.[21]

History

Main article: History of physics

Isaac Newton (1643-1727)

The philosopher Thales (ca. 624–546 BC) first refused to accept various supernatural, religious or mythological explanations for natural phenomena, proclaiming that every event had a natural cause. Early physical theories were largely couched in philosophical terms, and never verified by systematic experimental testing as is popular today. Many of the commonly accepted works of Ptolemy and Aristotle are not always found to match everyday observations.

Even so, many ancient philosophers and astronomers gave correct descriptions in atomism and astronomy. Leucippus (first half of 5th century BC) first proposed atomism, while Archimedes derived many correct quantitative descriptions of mechanics, statics and hydrostatics, including an explanation for the principle of the lever. The Middle Ages saw the emergence of an experimental physics taking shape among medieval Muslim physicists, the most famous being Alhazen, followed by modern physics largely taking shape among early modern European physicists, the most famous being Isaac Newton, who built on the works of Galileo Galilei and Johannes Kepler. In the 20th century, the work of Albert Einstein marked a new direction in physics that continues to the present day.

Core theories

Further information: Branches of physics, Classical physics, Modern physics, Topic outline of physics

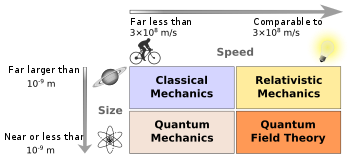

While physics deals with a wide variety of systems, certain theories are used by all physicists. Each of these theories were experimentally tested numerous times and found correct as an approximation of nature (within a certain domain of validity). For instance, the theory of classical mechanics accurately describes the motion of objects, provided they are much larger than atoms and moving at much less than the speed of light. These theories continue to be areas of active research, and a remarkable aspect of classical mechanics known as chaos was discovered in the 20th century, three centuries after the original formulation of classical mechanics by Isaac Newton (1642–1727).These central theories are important tools for research into more specialized topics, and any physicist, regardless of his or her specialization, is expected to be literate in them. These include classical mechanics, quantum mechanics, thermodynamics and statistical mechanics, electromagnetism, and special relativity.

Research fields

Contemporary research in physics can be broadly divided into condensed matter physics; atomic, molecular, and optical physics; particle physics; astrophysics; geophysics and biophysics. Some physics departments also support research in Physics education.Since the twentieth century, the individual fields of physics have become increasingly specialized, and today most physicists work in a single field for their entire careers. "Universalists" such as Albert Einstein (1879–1955) and Lev Landau (1908–1968), who worked in multiple fields of physics, are now very rare.[22]

Condensed matter

Main article: Condensed matter physics

Velocity-distribution data of a gas of rubidium atoms, confirming the discovery of a new phase of matter, the Bose–Einstein condensate

The most familiar examples of condensed phases are solids and liquids, which arise from the bonding and electromagnetic force between atoms. More exotic condensed phases include the superfluid and the Bose–Einstein condensate found in certain atomic systems at very low temperature, the superconducting phase exhibited by conduction electrons in certain materials, and the ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic phases of spins on atomic lattices.

Condensed matter physics is by far the largest field of contemporary physics. Historically, condensed matter physics grew out of solid-state physics, which is now considered one of its main subfields. The term condensed matter physics was apparently coined by Philip Anderson when he renamed his research group — previously solid-state theory — in 1967.

In 1978, the Division of Solid State Physics at the American Physical Society was renamed as the Division of Condensed Matter Physics.[23] Condensed matter physics has a large overlap with chemistry, materials science, nanotechnology and engineering.

Atomic, molecular, and optical physics

Main article: Atomic, molecular, and optical physics

Atomic, molecular, and optical physics (AMO) is the study of matter-matter and light-matter interactions on the scale of single atoms or structures containing a few atoms. The three areas are grouped together because of their interrelationships, the similarity of methods used, and the commonality of the energy scales that are relevant. All three areas include both classical and quantum treatments; they can treat their subject from a microscopic view (in contrast to a macroscopic view).Atomic physics studies the electron shells of atoms. Current research focuses on activities in quantum control, cooling and trapping of atoms and ions, low-temperature collision dynamics, the collective behavior of atoms in weakly interacting gases (Bose–Einstein Condensates and dilute Fermi degenerate systems), precision measurements of fundamental constants, and the effects of electron correlation on structure and dynamics. Atomic physics is influenced by the nucleus (see, e.g., hyperfine splitting), but intra-nuclear phenomenon such as fission and fusion are considered part of high energy physics.

Molecular physics focuses on multi-atomic structures and their internal and external interactions with matter and light. Optical physics is distinct from optics in that it tends to focus not on the control of classical light fields by macroscopic objects, but on the fundamental properties of optical fields and their interactions with matter in the microscopic realm.

High energy/particle physics

Main article: Particle physics

A simulated event in the CMS detector of the Large Hadron Collider, featuring a possible appearance of the Higgs boson.

Currently, the interactions of elementary particles are described by the Standard Model. The model accounts for the 12 known particles of matter (quarks and leptons) that interact via the strong, weak, and electromagnetic fundamental forces. Dynamics are described in terms of matter particles exchanging gauge bosons (gluons, W and Z bosons, and photons, respectively). The Standard Model also predicts a particle known as the Higgs boson, the existence of which has not yet been verified; as of 2010[update], searches for it are underway in the Tevatron at Fermilab and in the Large Hadron Collider at CERN.

Astrophysics

Main articles: Astrophysics and Physical cosmology

Astrophysics and astronomy are the application of the theories and methods of physics to the study of stellar structure, stellar evolution, the origin of the solar system, and related problems of cosmology. Because astrophysics is a broad subject, astrophysicists typically apply many disciplines of physics, including mechanics, electromagnetism, statistical mechanics, thermodynamics, quantum mechanics, relativity, nuclear and particle physics, and atomic and molecular physics.The discovery by Karl Jansky in 1931 that radio signals were emitted by celestial bodies initiated the science of radio astronomy. Most recently, the frontiers of astronomy have been expanded by space exploration. Perturbations and interference from the earth’s atmosphere make space-based observations necessary for infrared, ultraviolet, gamma-ray, and X-ray astronomy.

Physical cosmology is the study of the formation and evolution of the universe on its largest scales. Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity plays a central role in all modern cosmological theories. In the early 20th century, Hubble's discovery that the universe was expanding, as shown by the Hubble diagram, prompted rival explanations known as the steady state universe and the Big Bang.

The Big Bang was confirmed by the success of Big Bang nucleosynthesis and the discovery of the cosmic microwave background in 1964. The Big Bang model rests on two theoretical pillars: Albert Einstein's general relativity and the cosmological principle. Cosmologists have recently established the ΛCDM model of the evolution of the universe, which includes cosmic inflation, dark energy and dark matter.

Numerous possibilities and discoveries are anticipated to emerge from new data from the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope over the upcoming decade and vastly revise or clarify existing models of the Universe.[24][25] In particular, the potential for a tremendous discovery surrounding dark matter is possible over the next several years.[26] Fermi will search for evidence that dark matter is composed of weakly interacting massive particles, complementing similar experiments with the Large Hadron Collider and other underground detectors.

IBEX is already yielding new astrophysical discoveries: "No one knows what is creating the ENA (energetic neutral atoms) ribbon" along the termination shock of the solar wind, "but everyone agrees that it means the textbook picture of the heliosphere — in which the solar system's enveloping pocket filled with the solar wind's charged particles is plowing through the onrushing 'galactic wind' of the interstellar medium in the shape of a comet — is wrong."[27]

Fundamental physics

While physics aims to discover universal laws, its theories lie in explicit domains of applicability. Loosely speaking, the laws of classical physics accurately describe systems whose important length scales are greater than the atomic scale and whose motions are much slower than the speed of light. Outside of this domain, observations do not match their predictions. Albert Einstein contributed the framework of special relativity, which replaced notions of absolute time and space with spacetime and allowed an accurate description of systems whose components have speeds approaching the speed of light. Max Planck, Erwin Schrödinger, and others introduced quantum mechanics, a probabilistic notion of particles and interactions that allowed an accurate description of atomic and subatomic scales. Later, quantum field theory unified quantum mechanics and special relativity. General relativity allowed for a dynamical, curved spacetime, with which highly massive systems and the large-scale structure of the universe can be well described. General relativity has not yet been unified with the other fundamental descriptions; several candidates theories of quantum gravity are being developed.Application and influence

Main article: Applied physics

Applied physics is a general term for physics research which is intended for a particular use. An applied physics curriculum usually contains a few classes in an applied discipline, like geology or electrical engineering. It usually differs from engineering in that an applied physicist may not be designing something in particular, but rather is using physics or conducting physics research with the aim of developing new technologies or solving a problem.The approach is similar to that of applied mathematics. Applied physicists can also be interested in the use of physics for scientific research. For instance, people working on accelerator physics might seek to build better particle detectors for research in theoretical physics.

Physics is used heavily in engineering. For example, Statics, a subfield of mechanics, is used in the building of bridges and other structures. The understanding and use of acoustics results in better concert halls; similarly, the use of optics creates better optical devices. An understanding of physics makes for more realistic flight simulators, video games, and movies, and is often critical in forensic investigations.

With the standard consensus that the laws of physics are universal and do not change with time, physics can be used to study things that would ordinarily be mired in uncertainty. For example, in the study of the origin of the Earth, one can reasonably model Earth's mass, temperature, and rate of rotation, over time. It also allows for simulations in engineering which drastically speed up the development of a new technology.

But there is also considerable interdisciplinarity in the physicist's methods, and so many other important fields are influenced by physics: e.g. presently the fields of econophysics plays an important role, as well as sociophysics.

Current research

Further information: List of unsolved problems in physics

A typical event described by physics: a magnet levitating above a superconductor demonstrates the Meissner effect.

In condensed matter physics, an important unsolved theoretical problem is that of high-temperature superconductivity. Many condensed matter experiments are aiming to fabricate workable spintronics and quantum computers.

In particle physics, the first pieces of experimental evidence for physics beyond the Standard Model have begun to appear. Foremost among these are indications that neutrinos have non-zero mass. These experimental results appear to have solved the long-standing solar neutrino problem, and the physics of massive neutrinos remains an area of active theoretical and experimental research. Particle accelerators have begun probing energy scales in the TeV range, in which experimentalists are hoping to find evidence for the Higgs boson and supersymmetric particles.[28]

Theoretical attempts to unify quantum mechanics and general relativity into a single theory of quantum gravity, a program ongoing for over half a century, have not yet been decisively resolved. The current leading candidates are M-theory, superstring theory and loop quantum gravity.

Many astronomical and cosmological phenomena have yet to be satisfactorily explained, including the existence of ultra-high energy cosmic rays, the baryon asymmetry, the acceleration of the universe and the anomalous rotation rates of galaxies.

Although much progress has been made in high-energy, quantum, and astronomical physics, many everyday phenomena involving complexity, chaos, or turbulence are still poorly understood.[citation needed] Complex problems that seem like they could be solved by a clever application of dynamics and mechanics remain unsolved; examples include the formation of sandpiles, nodes in trickling water, the shape of water droplets, mechanisms of surface tension catastrophes, and self-sorting in shaken heterogeneous collections.[citation needed]

These complex phenomena have received growing attention since the 1970s for several reasons, including the availability of modern mathematical methods and computers, which enabled complex systems to be modeled in new ways. Complex physics has become part of increasingly interdisciplinary research, as exemplified by the study of turbulence in aerodynamics and the observation of pattern formation in biological systems. In 1932, Horace Lamb said:[29]

I am an old man now, and when I die and go to heaven there are two matters on which I hope for enlightenment. One is quantum electrodynamics, and the other is the turbulent motion of fluids. And about the former I am rather optimistic.

No comments:

Post a Comment